Pointers

I feel like pointers are very easy to understand, but you need to be skilled to use them effectively. But what

Exactly is a Pointer?

Pointers are exactly what they are named after. It is something that points to something. In this case, pointers point to a location in memory of some other variable.

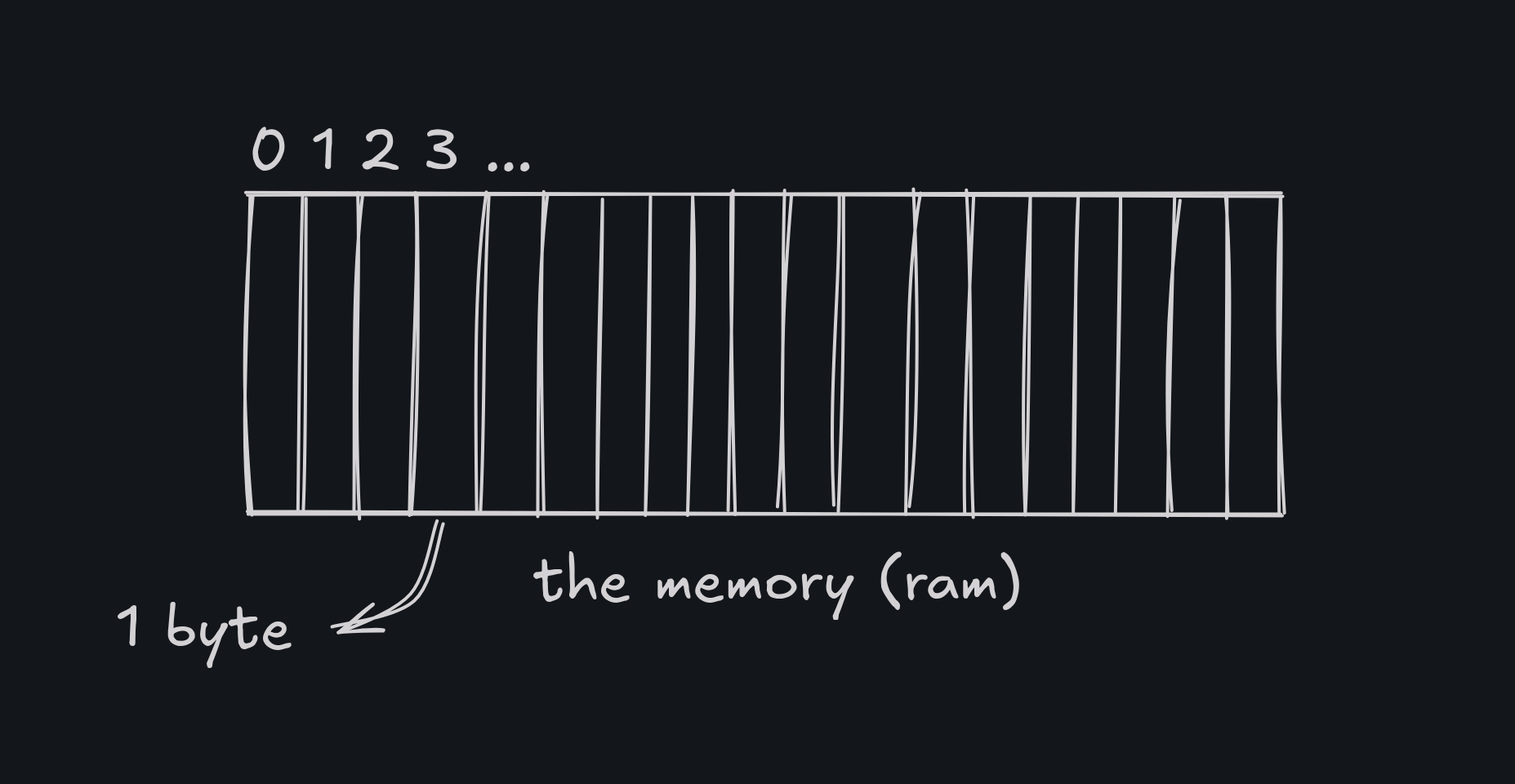

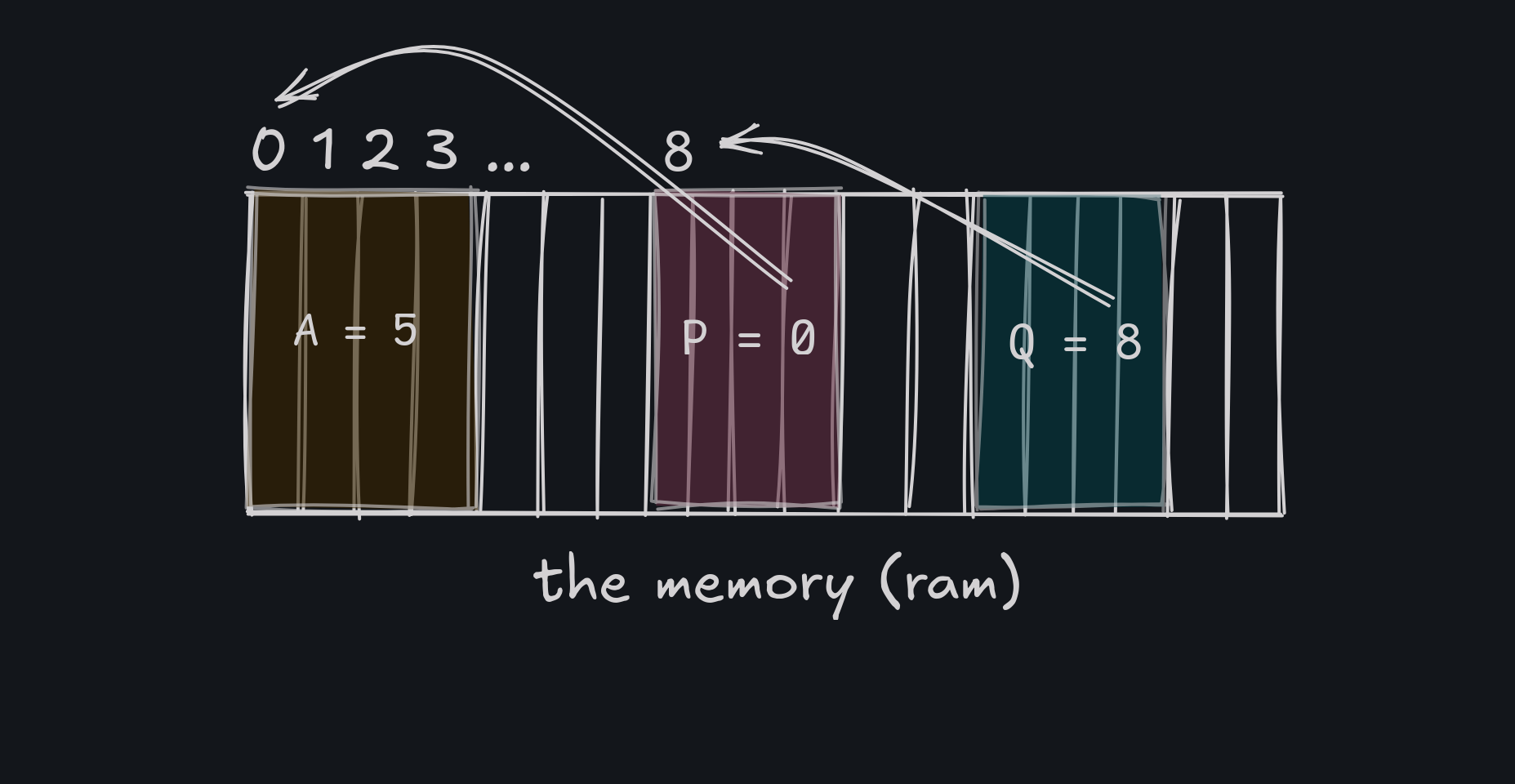

Your RAM, the memory has a lot of cells. Let us assume that each cell is of 1 byte. Each cell has an address. The address of the first cell is 0, the second cell is 1, and so on.

When we declare a integer, 4 bytes are allocated to it, for a float, it is also 4 bytes and chars are 1 byte.

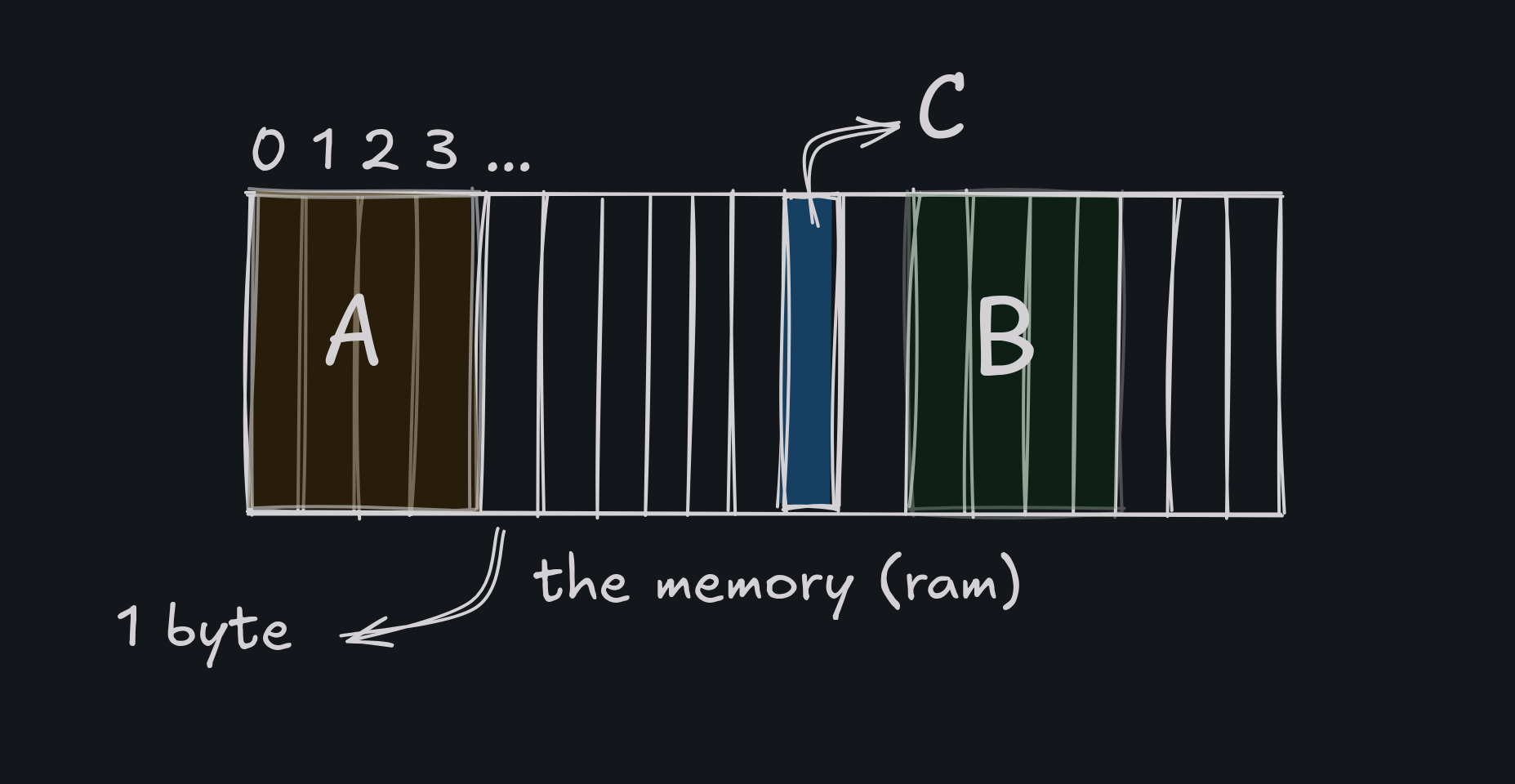

int A;

float B;

char C;The above code will look something like this in memory:

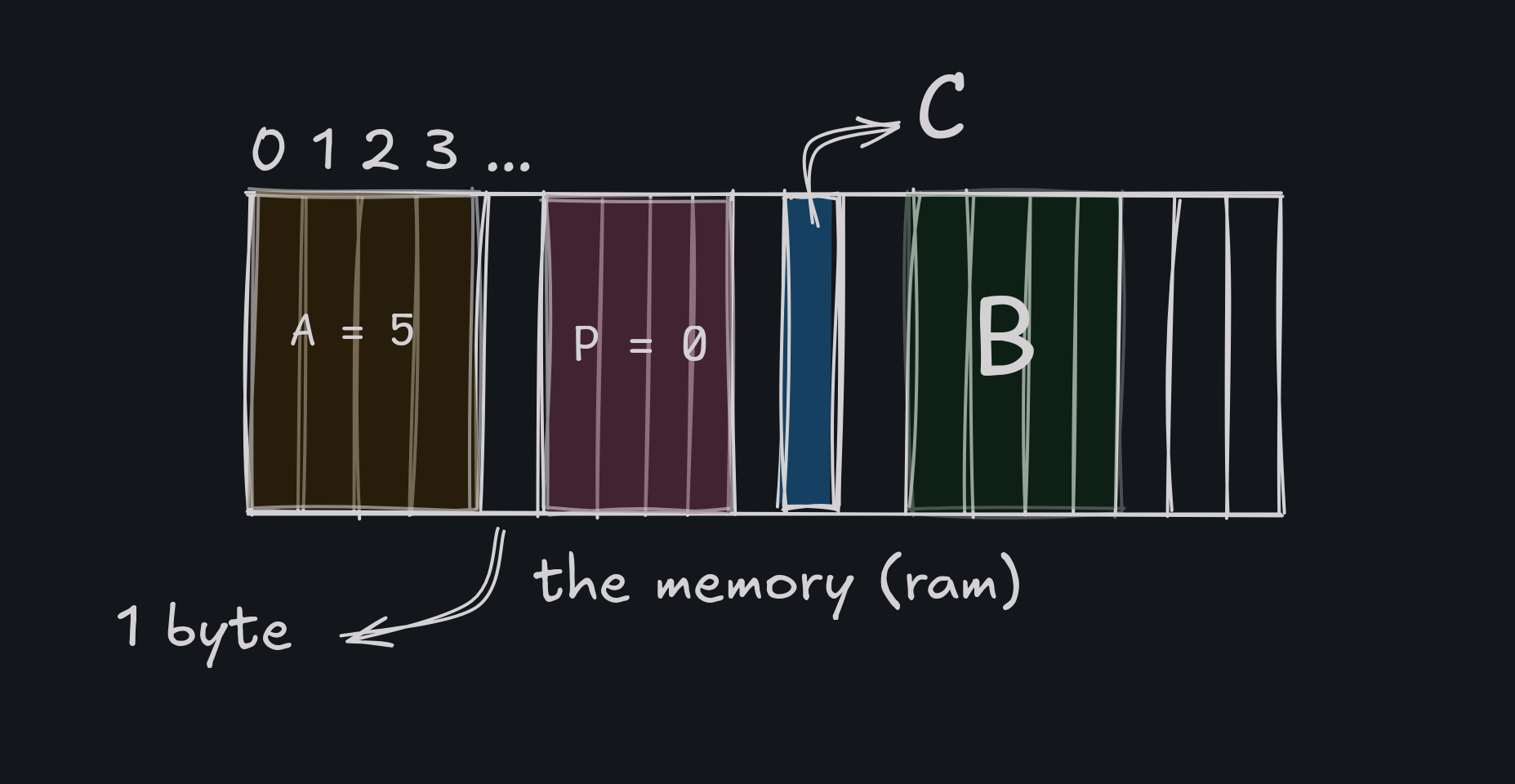

A = 5;Now when we assign a value to the variable A, the compiler goes to the lookup table, gets the address of A, which in this case would be 0, and stores the value of 5 in those 4 bytes. Everytime the value of A is called or changed, the compiler goes to the address 0 and does the necessary operations.

Let us now introduce pointers.

int *P;

P = &A; // & returns the address of the variableThis can also be said as P is a pointer to an integer. In the second line, we are assigning the address of A to P. So now, P points to the address of A which in this case is 0.

This is how the memory currently looks like:

Now that we have a pointer, we can do a lot of things with it. But first lets print out the pointer. Predict the output.

printf("%d", P);

printf("%d", *P);$ ./main

0

5So we can actually find out the value of A with the notation of *P. This is called dereferencing a pointer. Now if we do

*P = 10;

printf("%d", A);$ ./main

10We will see that the value of variable A changes.

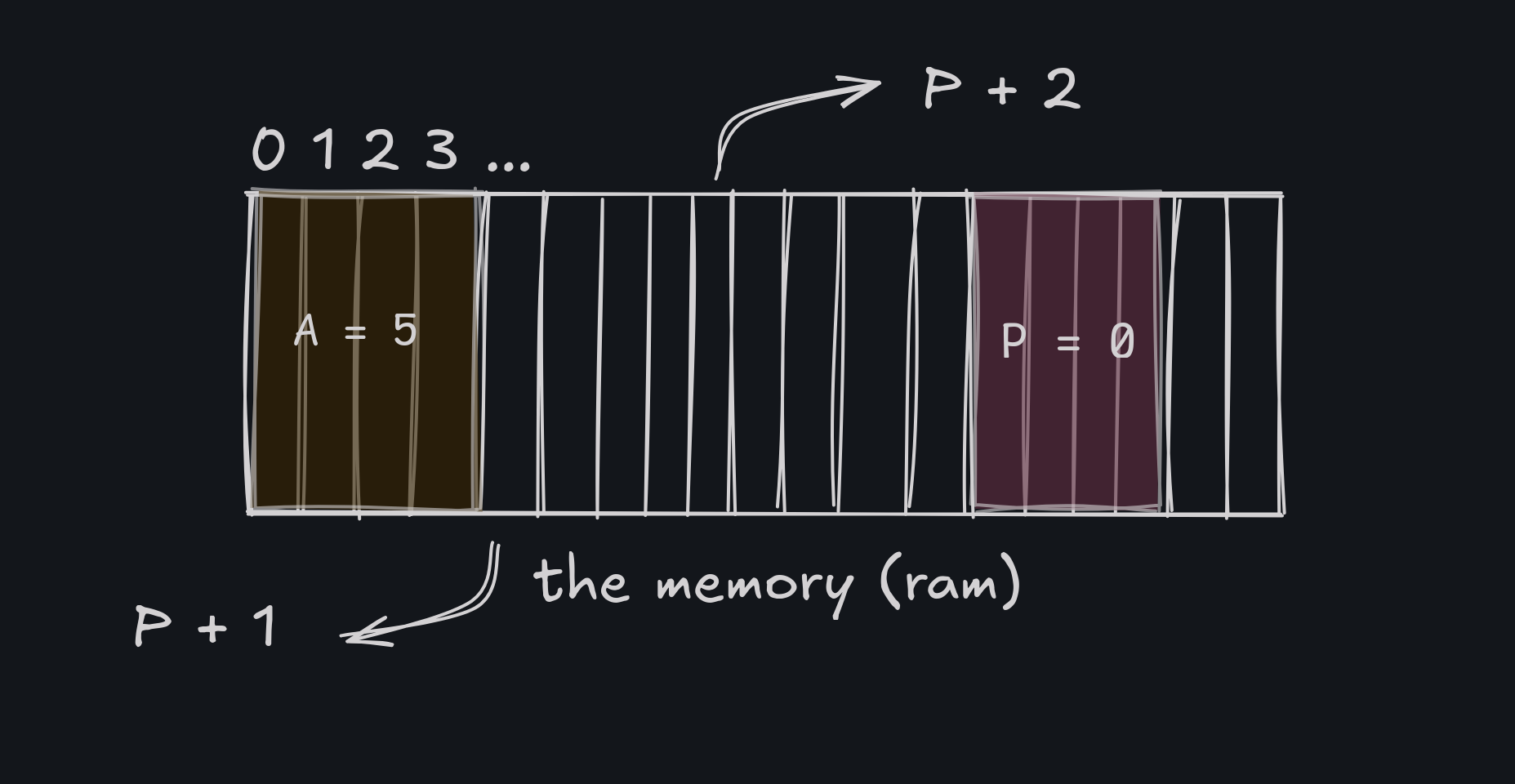

Pointers and Maths

We know the value of P is 0. What would be the value of P + 1 ? Well all it does is returns the next availble address for an integer. As the blocks 0 - 3 are already taken by A, the next available address is 4. So the value of P + 1 is 4. Similarly, P + 2 would be 8 and so on.

But what if we tried to print *(P + 1)? As we have not allocated any value to the address 4, it would return a garbage value. So it is always better to allocate memory to the address before using it.

Pointers to Pointers

Let us take a look at the following code

int A = 5;

int *P = &A;

int **Q = &P;Now this is how the arrangement looks like in memory:

This can be read as Q is a pointer to a pointer to an integer. So Q points to the address of P, which in turn points to the address of A. This can be chained to any number of pointers.

Pointers as Arguments

Let us take a look at this code

void square(int x){

printf("%d", &x); // different

x = x * x;

}

int main() {

int x = 5;

printf("%d", &x); // different

square(x);

printf("%d", x);

return 0;

}The output of the code is 5. Anyone who has done a little bit of C should be able to reach this conclusion. But here is how it actually works.

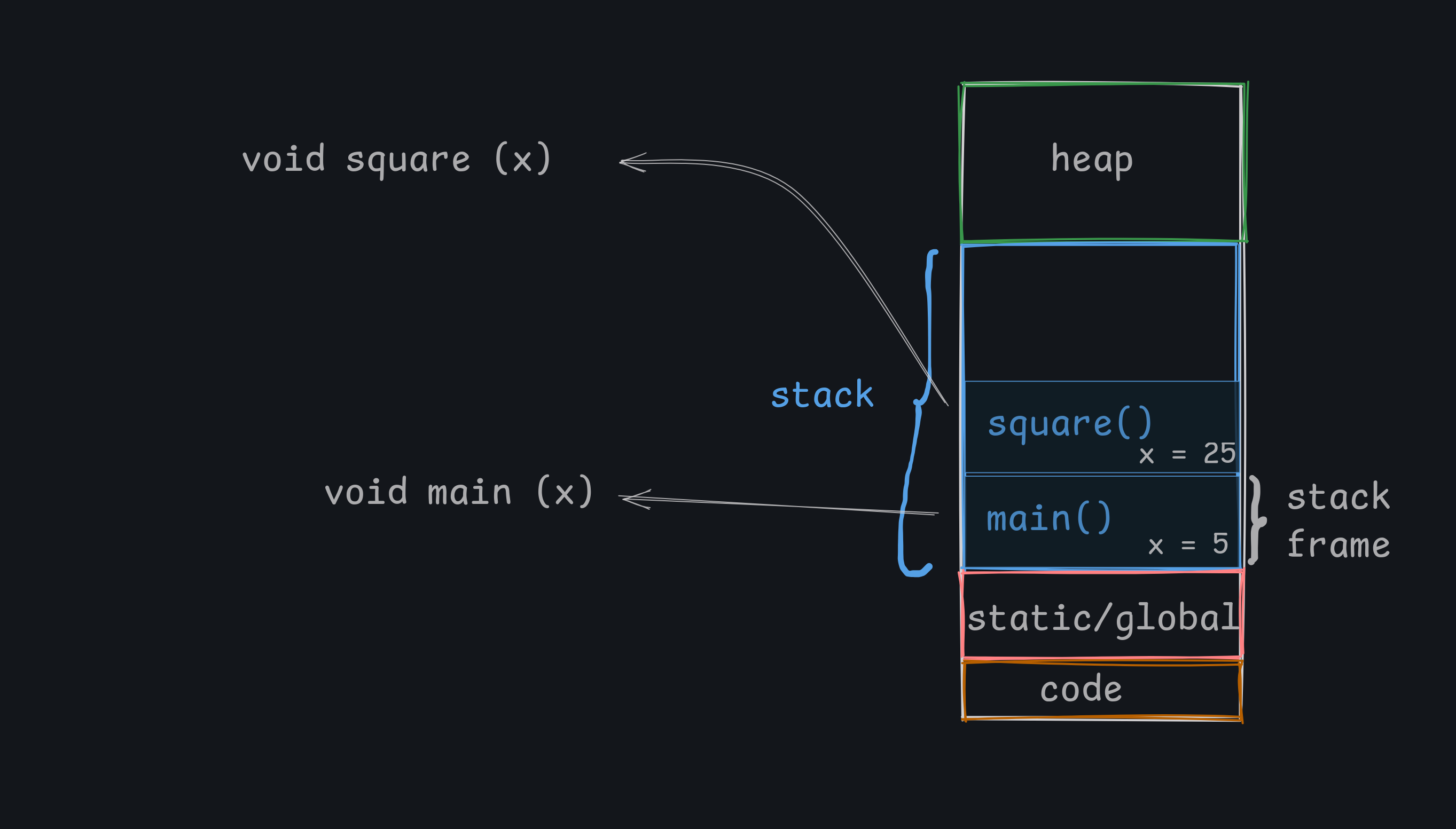

There are four parts of an application's memory.

- Heap

- Stack

- Static/Global Vars

- The Code

For this code execution, we are mostly going to focus on the stack. Now when the function square is called, a new stack frame is created. The value of x is copied to the stack frame and the operations are done on the stack frame. So the value of x in the main function is not changed. We can see that by printing the adresses of x in both functions.

Stack frames are just a way to keep track of the function calls. When a function is called, a new stack frame is created and when the function is done, the stack frame is destroyed.

To get the desired the result of squaring the number, we will have to use pointers.

void square(int *p){

*p = (*p) * p;

}

int main() {

int x = 5;

square(&x);

printf("%d", x); // 25

return 0;

}So instead of passing the value of x, we are passing the address of x. This method is called pass/call by reference. This is because we are passing the reference of the variable x to the function. This is the most common way of using pointers in functions.

This method is also helpful in saving memory because in the earlier implementation, when the square function stack frame was called, another 4 bytes had to be allocated for integer. But in this case, only 4 bytes are allocated for the address of x.

Pointers and Arrays

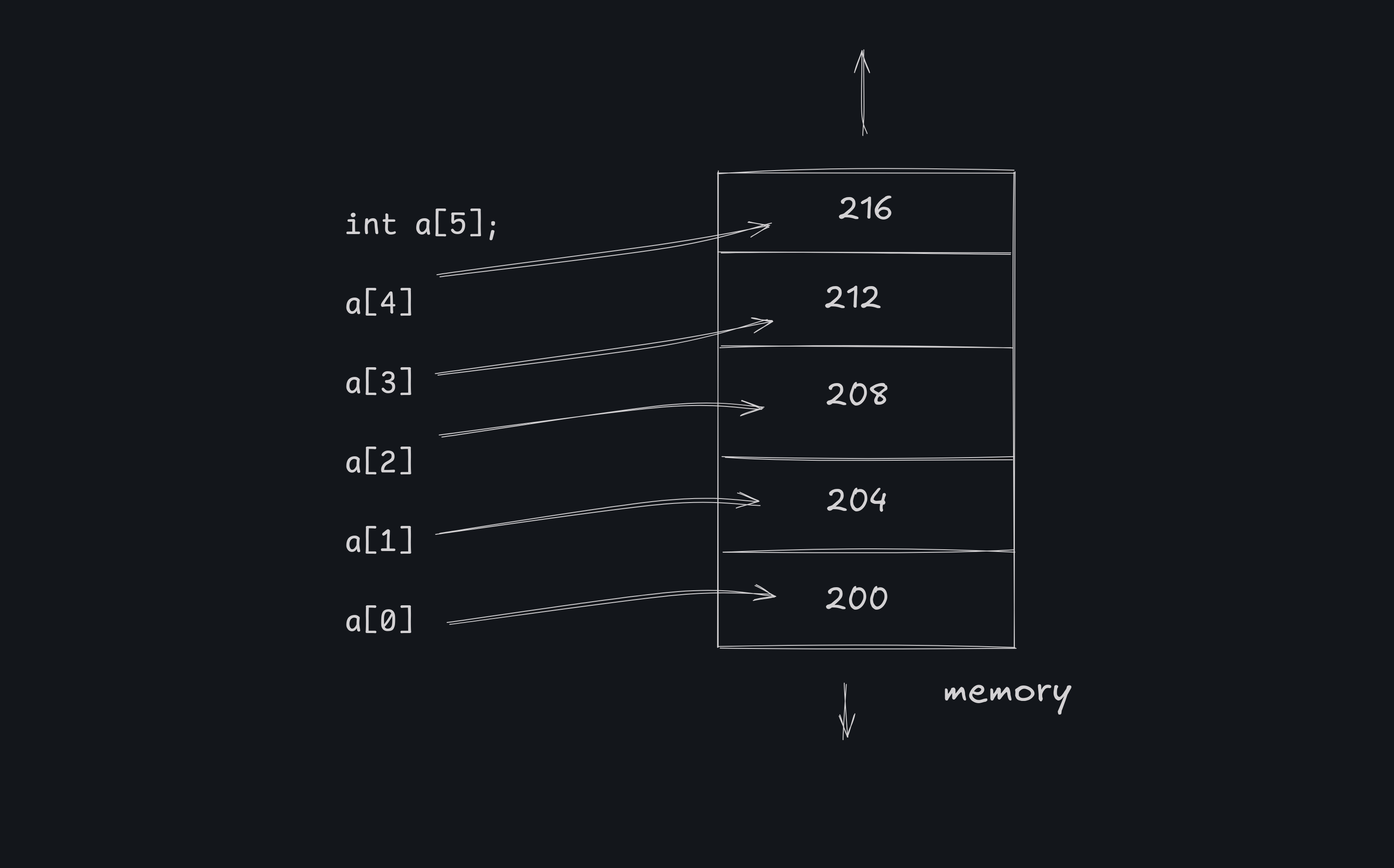

Let us have an integer array with 5 elements. The overall size of the array would be 20 consecutive bytes. If the first element is at address 200, then the second is at 204, the third at 208 and so on.

int A[5] = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

int *P = &A[0]; // This can also be written as int *P = A;

printf("%d", *P); // 10

printf("%d", *(P + 1)); // 20We have already seen that P + 1 returns the next available address for an integer. So *(P + 1) returns the value at that address. And P + 1 is 4 more than P. So P + 1 becomes the address of A[1]. By this logic, *(P + 2) would be 30 and so on. We can make out that

ITEM at index i = A[i] = *(A + i)

ADDRESS of item at index i = &A[i] = A + iArrays as Arguments

Take a look at the following code

int sum(int A[]){

int s = 0;

int size = sizeof(A)/sizeof(A[0]);

for(int i = 0; i < size; i++){

s += A[i];

}

return s;

}

int main() {

int A[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

printf("%d", sum(A));

return 0;

}Even though it should be 15, the output is 1. When the compiler sees an array as a function arguement, it does not copy the whole array, it just creates a pointer to the datatype of the array and the compiler copies the address of the first element in the array.

Arrays are always called by reference. The compiler implicitly converts the array to a pointer. So the size of the array is not known in the function. A much better solution is to pass the size as an argument.

int sum(int *A, int size){

int s = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < size; i++){

s += A[i];

}

return s;

}

int main() {

int A[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int size = sizeof(A)/sizeof(A[0]);

printf("%d", sum(A, size)); // works as expected - 15

return 0;

}Character Arrays

For most of the part, character arrays are treated the same way as integer arrays. One difference is that the character arrays are always null terminated. This means that the last element of the array is always \0. This is used to denote the end of the string.

char A[4]

A[0] = 'j';

A[1] = 'a';

A[2] = 'k';

A[3] = 'e';

printf("%s", A); // random garbage because string is not null terminatedinstead we have to do

char A[5]

A[0] = 'j';

A[1] = 'a';

A[2] = 'k';

A[3] = 'e';

A[4] = '\0';

printf("%s", A); // jakeExample of using pointers with character arrays. By now this should be easy to understand.

void print(char *c) {

while (*c != '\0') {

printf("%c", *c);

c++;

}

}

int main() {

char c[20] = "jake";

print(c);

return 0;

}Pointers and Multidimensional Arrays

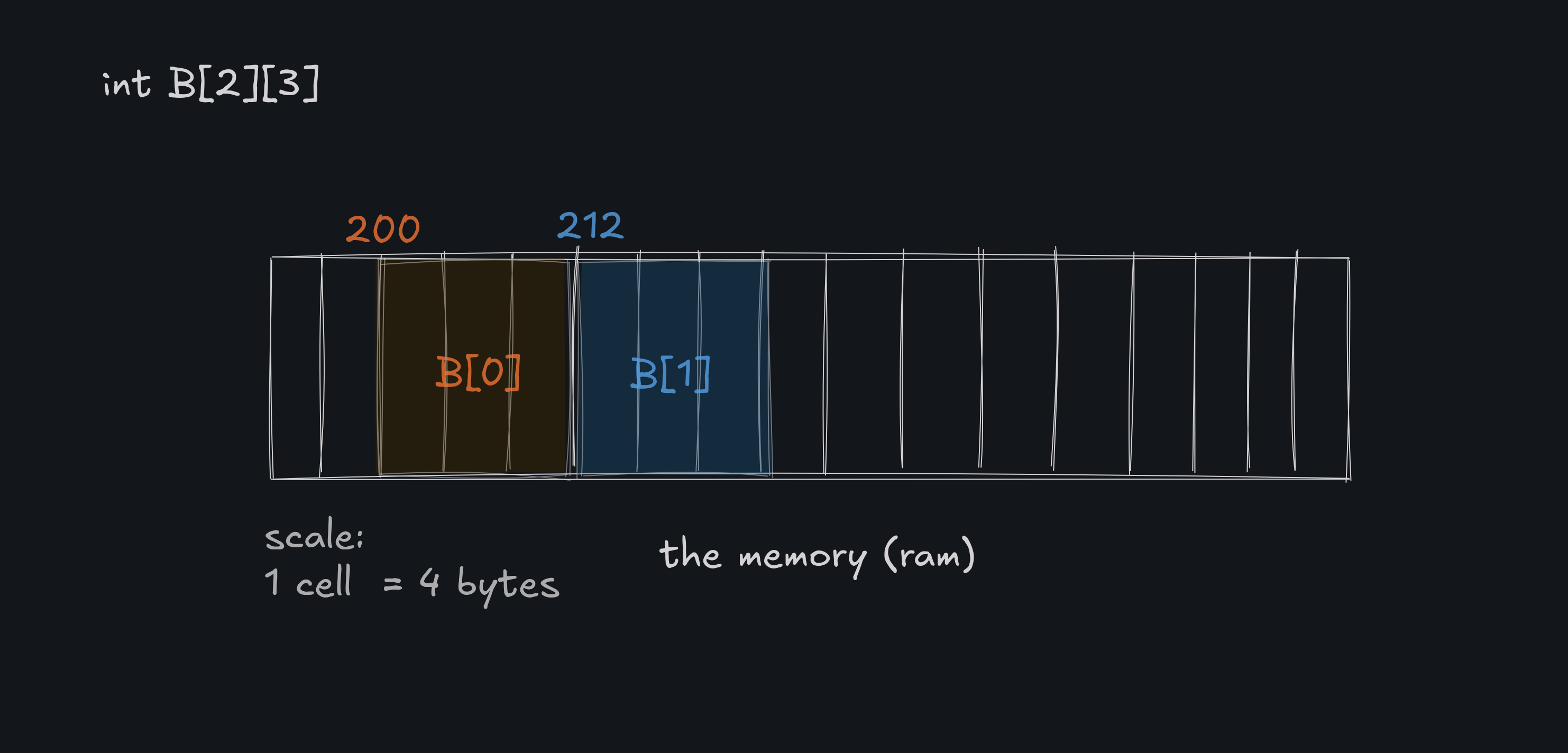

When we declare a multidimensional array, for example

int b[2][3];it means that we have 2 arrays of 3 integers each. The memory is allocated in a row major order. So if the first array is at 200, the second at 212 and so on. So b[1][2] is at 12 + 2 * 4 = 20. In the memory, it kinda looks like this

Now if we try to declare

int *p = b;We will get an error because *p is pointer to an integer and b will return a pointer to an 1d array of integers. If we print B or &B[0], we will get the address of the first array, which in this case is 200. Here we can also notice that we can write

B[i][j] = *(B[i] + j) = *(*(B + i) + j)Pointers as Function Returns

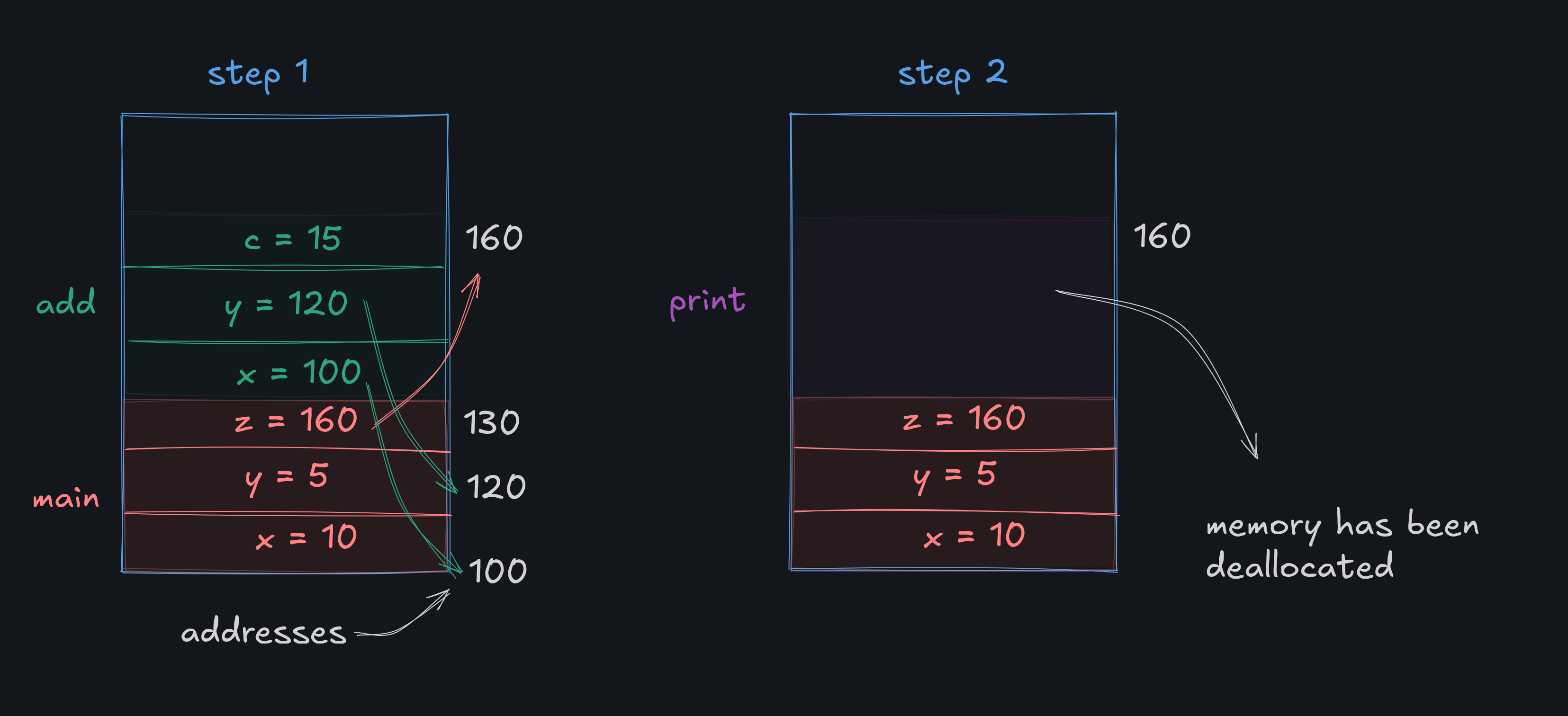

Take a look at the following C code

int add(int* a, int* b) {

int c = *a + *b;

return c;

}

int main() {

int x = 10, y = 5;

int z = add(&x, &y);

printf("%d", z);

return 0;

}We know how this code is not efficient because the value of c is copied to z, which is not needed. Instead we can return the address of c. For some reason, I will also add an arbitrary function in between.

void print() {

printf("Hello World!\n");

}

int* add(int* a, int* b) {

int c = *a + *b;

return &c;

}

int main() {

int x = 10, y = 5;

int *z = add(&x, &y);

print();

printf("%d", *z);

return 0;

}Well the expected output should be

Hello World

15But we will see that instead of 15, a garbage value is printed in the console. So what even just happened here.

After the function add is called, the stack frame is destroyed and the memory is deallocated. So the address of c is no longer valid. That deallocated memory is then consumed by the print function, and the memory is being overwritten. This is why we get a garbage value.

So the correct way to do this would be to allocate memory dynamically. After reading that post, you can solve this by

void print() {

printf("Hello World!\n");

}

int* add(int* a, int* b) {

int* c = (int*)malloc(sizeof(int));

*c = *a + *b;

return &c;

}

int main() {

int x = 10, y = 5;

int *z = add(&x, &y);

print();

printf("%d", *z);

return 0;

}Function Pointers and Callbacks

Pointers can also point to functions. This is useful when we want to pass a function as an argument to another function. Let us just start with a simple example.

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int main() {

int (*p)(int, int);

p = &add;

printf("%d", p(2, 3));

return 0;

}Be sure to put the * in the parenthesis otherwise it would become a function that returns a pointer to an integer. The whole point of using function pointers is so that we can pass functions as arguments to other functions and also to return functions from functions.

void A() {

printf("Hello\n");

}

void B(void (*ptr)()) { // function pointer as argument

ptr(); // call-back function that "ptr" points to

}

int main() {

B(A); // passing address of the function

return 0;

}This should be more than enough to understand the basics of pointers. The next part will be about dynamic memory allocation where pointers will return again.